The Beginning of Black Public Education in Florida

After the Civil War African American’s placed a priority on free public education as a condition of their freedom from bondage. In 1868 Assistant Commissioner of the Freedman’s Bureau Col. John T. Sprague reported, “there is no abatement in the desire shown by the freedmen for their own education and that of their children.”

Black citizens in Florida lobbied and state politicians responded by creating a system of free public education in Florida through the Florida Constitution of 1869 and state laws passed in 1869.

The Civil Rights Act of 1873 passed by the Florida Legislature banned racial discrimination in all public schools in Florida.

Source: Joe M. Richardson, The Negro in the Reconstruction of Florida, 1865-1877 Tallahassee: Florida State University, 1965.

Photo Source, “Freedman School 1863-1865, possible South Carolina. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540

Racial Segregation in Florida

With the passing of the 1885 Florida Constitution public and private schools would be segregated by race (Section 12). Subsequent legislation passed in 1895 and 1913 would enforce strict separation of the races in the classroom including barring white teachers and administrators from all black public and private schools.

Pictured: 1885 Florida Constitution, sections 12-15. Florida Memory, Florida State Archives, Constitution of 1885.

Orlando Colored School

Jones High School was first admitted to the Orlando County Public School Board in the 1880s as the Orlando Colored Academy.

All black students in the county who wanted to go to high school went there.

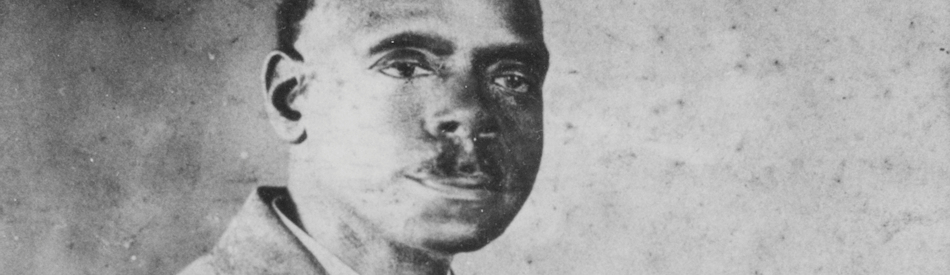

John T. Stuften was principal from 1891 until 1894. He was the first black lawyer in Orlando during the 1880s and 1890s and believed that education and thrift would deliver freedom and acceptance to African Americans in the segregated South.

Pictured: John T. Stuften, photo courtesy of Florida Memory, State of Florida Archives in Tallahassee.

Johnson Academy

Established in 1895, the school now known as Jones High School was first an old frame building on the southwest corner of Garland Avenue and Church Street.

The school was moved to the corner of Jefferson and Chatham Streets and renamed Johnson Academy in honor of the principal Lymus Johnson.

Pictured Johnson Academy Teachers, n.d. Jones High School Historical Society

World War I

Administrators, teachers and students at Johnson Academy participated in the war effort by supporting the home front.

Johnson Academy raised $16.54 for the Red Cross in 1918 and in the same year held an event to raise money for war saving stamps.

By 1918 the Orange County School Board doubled the size of Johnson Academy, employed ten teachers and enlarged the building so it could fit up to four hundred students.

William Easton Jordan was born in 1895 and served admirably in World War I. He served in the 92nd Infantry Division (nicknamed the Buffalo Soldiers) and the 809th Pioneer Infantry Regiment and served on the war front in France. He was born in Orlando and was a student at Johnson Academy. The Orange County Draft Board in 1918 noted his occupation was “clerk” which meant he had an education in reading and math which was also recorded in the 1930 US Census where he was noted to be a local Orlando merchant.

Pictured: Service card for William Easton Jordan during World War I. Florida Memory WWI Service Cards, State of Florida Archives.

First Jones High School

In 1912, L.C. Jones became principal of Johnson Academy. Under his leadership, a new school was built in 1921 on the corner of Washington Street and Parramore Avenue. Because his family donated the land for the school, the school was renamed Jones High School. In 1931, Jones High School had its first graduation of students completing the twelfth grade.

Pictured L.C. Jones. Jones High School Historical Society

The Colored School Curriculum

Throughout the South in segregated black schools, the curriculum was focused around industrial and agricultural education. White schools included a liberal arts education missing from the segregated black schools. Segregated black schools throughout the South quietly taught a liberal arts curriculum along side an industrial arts program under fear if local or state officials found out their course work was based in literature, mathematics, Latin or science funding from the state and local governments would be at threat. At Jones before the 1950s teachers taught Latin, Mathematics, Geometry, Biology, Chemistry and Oratory to students in addition to the agriculture and industrial arts required by the state and county school systems. The school year was also a few months shorter for black students than white students in Orlando until the 1940s. “We were taught that a liberal arts education was necessary, not just for getting a job, but just to make a person aware of his environment and his history and so on…”Audrey Reicherts (Class of 1947)

(Class of 1947-Quoted in Benjamin Brotemarkle Crossing Division Street: An Oral History of the African American Community in Orlando, original interview September 2001)

Pictured: Educational Survey Commission of the State of Florida, “Digest Survey Staff Report Elementary and Secondary Education” State Archives of Florida 1928

Click "View More" to enlarge the image.

National Negro Health Week

Educator and national African American leader Booker T. Washington launched National Negro Health Week in 1915 and was held annually in large cities and towns by black residents until the 1950s. African American leaders in Orlando sponsored the first Negro Health Week in 1922 and held it annually the first week of April until 1950. Jones High School participated in neighborhood clean up programs while state and local officials held programs for students at Jones High School to learn about healthy living and avoiding illness until the 1940s when those programs moved to the 1940s when those programs moved to the Community Betterment Center in Parramore. During the last Negro Health Week in 1950, teachers and students at Jones High School held a memorial to recognize Booker T. Washington and his efforts with National Negro Health Week.

Learn more about National Negro Health Week at the National Archives by clicking here.

Pictured: Jones High School students from the 1920s, Jones High School Historical Society

Mary McLeod Bethune

Mary McLeod Bethune spoke at Jones High School on September 23rd, 1927. Jones High School was the center of the community and would host speakers like Bethune as well as other city wide events for African Americans in Orlando.

Pictured: Mary McLeod Bethune with graduating class, 1928 Florida Memory, State of Florida Archives Tallahassee Florida.

The High School Grades

“Jones High School was a good high school, it’s still a good high school. I went to Jones High School from early childhood to 1925-26, and that’s the time we graduated tenth grade. We were not going to the twelfth grade then. We had not reached that point in Orlando. There were some schools, some cities that did not go any further than eighth and ninth.

Pictured: Jones High School Tenth Grade Class from 1928. Source “Jones High School Through the Ages”

World War II

Principal Banks and the Jones High School Athletic Program raised over $1,500 for war bonds in 1944 & 1945 by donating portions of the money raised at athletic events. Jones High School was also the location for recruiting efforts for Parramore residents to volunteer in civilian and military capacities during the war.

Pictured: The Original Building of Jones High School from 1949, Jones High School Historical Society

Jones High “The Neighborhood School”

L. C. Jones along with the teachers and parents of Parramore wanted Jones High School to be a “neighborhood school.” This meant that the administrators, teachers, parents and students all lived in the same neighborhood and worshipped at the same churches. Residential segregation kept African Americans in the neighborhood and Jones High School was not only a school but a central community center for the residents of Parramore. Edna W. Coleman (class of 1932) recalled, “It was—what shall I say—family-orientated…Teachers were mostly surrogate mothers to the kids…They felt they needed it.” Before the 1950s, Jones High School was the location of special events, black celebrities would speak and perform at Jones for the Parramore community. Jones High School hosted evening vocational classes where adults could earn certificates in domestic trades such as cooking and maid service. Audrey Reicherts (class of 1947) remembered, “At one time, when I was growing up here in Orlando, Jones High School was, well, a cultural center because concerts were held there in the auditorium and outstanding events in the African-American community were held there and it was kind of a focal point for the activities of the for the African-American community.”

Quotes from Jones High School Centennial Celebration and Benjamin Brotemarkle Crossing Division Street: An Oral History of the African American Community in Orlando (original interview September 2001)

Pictured: Jones High School class of 1931, the first 12th grade class to graduate from the school. Jones High School Historical Society

The New Jones High School 1952

By the end of the 1940s, white local and state officials throughout Florida anticipated the Federal Government demanding racial integration as President Truman did with the US military and as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People began a successful legal campaign to end racial segregation in education that cumulated in the Brown v. Board Decision in 1954. In an effort to quell demands for racial integration and equality, white state and local officials put more money into black education in Florida and built news schools in hopes that the “separate but equal” doctrine to Jim Crow segregation would leave Florida’s school system segregated. In 1950 the Orange County School Board approved the building of new Jones High School and the original Jones High School would remain an elementary school named Callahan Elementary.

Pictured: Jones High School from 1957

A New Era Begins

The end of racial segregation in Orange County Schools and the integration of those school was a slow and decades long process you could even say an unfinished project. The Florida Teachers Association was a black profession organization that represented teachers and from 1938 to 1943 they fought local school systems to equalize the pay of white and black teachers throughout the state.

The Florida Department of Education and the Superintendent of Public Instruction, Tom Bailey, launched the Minimum Foundation Program in 1947 which required local county school systems to spend more on black students and racially segregated school facilities than in the past so that total monies spent on black education in public school would increase. State officials did this to demonstrate that Florida was committed to the “equal” in the separate but equal doctrine in hopes of stopping federal legislation or any court decisions to end racial segregation in public schools. The plan for a brand new Jones High School building with updated facilities would be a response to this effort.

Pictured: Jones High School in 1949 from Orlando Negro Chamber of Commerce, Orlando Negro Chamber of Commerce Business Directory (Orlando: Orlando Negro Chamber of Commerce, 1949) from Orlando Memory Online

New School, Same Old Feelings

In 1950, the Orange County School Board first proposed the New Jones High School to be built at the corner of Gore Street and Orange Blossom Trail (Hwy 441) in Parramore but the area selected was “zoned white.” Five hundred white protesters demanded the school board move the proposed location to Washington Shores a black neighborhood further from where most of the students lived and a more expensive location. The administrators, teachers, parents and students lobbied the school board to keep the original Gore Street location. They ultimately prevailed.

Months before the new Jones High School was completed, on February 9, 1952 the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan held a rally and burned a cross just outside of the city limits to rally and try to intimidate Orlando’s African American community. Bill Hendrix a candidate for governor in 1952 and Grand Dragon of the Florida KKK was the featured speaker and warned local residents that Florida will need “a few more lynchings…"

Source: Source Orlando Sentinel February 11, 1952

Pictured: Aerial view of Jones High School 1962 featured in the Sixteenth Annual North State Band Festival Program, Florida Association of Band Directors

New Jones High School 1952

The new Jones High School was completed in May of 1952. The school was dedicated on November 23rd, 1952. When the new school opened, there were 903 students and 35 teachers at Jones High School. The auditorium could seat 1,200 people. The gymnasium held 2,000 people. The old school became Callahan Elementary and served the primary grades.

“My first year at the "old" Jones High had been an exciting year in my life, but it paled in comparison to the move to the ''new" Jones High. The new school was the talk of the entire black community. Indeed, it was a new experience for the principal, teachers, students and parents. Attending the ''new" Jones High meant walking in a new direction, through new neighborhoods, with new friends and new experiences.” Cornelia McGowan Bright (Class of 1957)

Source Monroe Fordham, ed. “We Remember” Jones High School Historical Society Inc. 2006

Pictured: A scene of Jones High School from the 1970s, Jones High School Historical Society

New Jones High School 1952

“Entering the "new" Jones High was an experience like none other. I thought that I had died and gone to heaven. All of the space, the modern class rooms, the modern facilities, the auditorium, the gym, the cafeteria; I thought that it couldn't get much better than this.” Thomas L. Ervin (Class of 1957)

“The "new" Jones High School was beautiful. Of course it was not as well equipped as the white schools and the books were somewhat out of date, but, again, the teachers were first-rate. They gave us lots of home work and graded us very strictly. I still remember names like Dudley, Braboy, Reddick, McClendon, Smith, Amati, etc. They really challenged us to do our· best. They never told us that we should not pursue a career that interested us. Some of my college classmates told me that their teachers told them that they should avoid certain career choices because no blacks were currently employed in those fields. What a shame! Just look at us now! Thomas A. Love (Class of 1957)

Source Monroe Fordham, ed. “We Remember” Jones High School Historical Society Inc. 2006

Pictured: Home Economics Classroom in 1957. From the Jones High School 1957 Yearbook, Jones High School Historical Society

New Jones High School 1952

“I was really excited about entering a brand new school as an 8th grader. However; I was not enthusiastic about the long walk that was required to get to school. Getting to Holden Street had been a long walk, but the "new" Jones High was even farther from my home. Sometimes my father would drop me off at the gate to the school on his way to work.” Cleather J. Marshall (Class or 1957)

“The thing that I remember first about the ''new" Jones High was the extremely long distance that I had to walk to get to school. I lived at the upper northern edge of the Orlando black community, and the school was located, clear across town, at the southern and western edge of the black community. It couldn't have been located any further from my house. Even people who lived in the southern part of the community had a long walk. · Then too, it was on the other side of one of Orlando's major highways.” Thomas L. Greene (Class of 1957)

“My family lived in the Lake Mann Housing Project. I walked to school every day. I remember the long walk down Orange Center Blvd. At that time, there was nothing on Orange Center Blvd. but cows, horses, and orange groves. It was a long walk, but all of the high school students from the Lake Mann Project walked along that road and there were no sidewalks.” Wilma Elvira Hill Aleem (Class of 1957)

Source Monroe Fordham, ed. “We Remember” Jones High School Historical Society Inc. 2006

Click "view more" to see the map on Google Maps.

Integration in Orlando

In 1954, with the new campus just two years old, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregated education was unconstitutional in the Brown v. Board Decision. The ruling landed like a bomb with a long fuse. A black high school such as Jones was bound to be affected, but at first nothing changed. It would be almost 10 years before the ruling affected Orlando. In 1962, eight black children and their parents sued in a case called Ellis v. Orange County School Board. On September 18, 1962 18 black students enrolled at all-white Durrance Elementary School in Orlando. It would take a series of court battles, however, to integrate the rest of Orange County.

From “Jones High School Centennial Celebration” (1995)

Pictured: The Russell Daily News (Russell, Kansas), Monday, May 17, 1954. Historic Events Newspaper Collection, Serial and Government Publications Division, Library of Congress

Civil Rights

In 1960, a group of students from Jones High School, which included Rev. Jim Perry (class of 1960) staged a sit-in demonstration at the Big Apple City Market on Orange Blossom Trail. Perry and other Jones High School students were active in the NAACP Youth Council started in 1959 by Rev. Nelson Pinder. In 1962, students from Jones High School were arrested after a sit-in at Moses Pharmacy on Orange Blossom Trail, Emrich’s Orlando Pharmacy on Church Street, and Stroud’s Rexall Drug Store on Orange Avenue. Those arrested included Sylvester Mack (Class or 1962) Sandra Poston (Class or 1962) and Louise Dinkins (Class of 1964). On March 6th, 1964 Martin Luther King Jr. came to Orlando and gave a speech at Tinker Field.

Pictured: From left to right: John Truesdell, Frank O’Neill, Mabel Richardson, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Sandra Poston Johnson (Class or 1962), Rev. Jim Perry (Class of 1960) and Rosemary Budley at the steps of the Shiloh Baptist Church in Orlando March 6, 1964. Photo from the Jones High School Historical Society.

Integration in Orlando

Desegregation was supposed to bring black and white students together. In Orange County, as in many areas where lawsuits were filed, it came to mean moving black students to white schools. Three of four black high schools were converted to other uses. Jones might have been sacrificed, too, but for the boycott of 1969 and subsequent protests whenever such plans were mentioned. Even so, Jones would be weakened—almost fatally so.

From “Jones High School Centennial Celebration” (1995)

Pictured: Page from the 1971 Jones High School Yearbook

Integration in Orlando

A January weekend in 1970 brought one of the most devastating changes. Frustrated that teachers still segregated, a federal judge gave Orange County a final deadline for integrating its staff. The result was a last-minute swap of teachers that came to be known as the “fish bowl.” Officials dropped teachers’ names into clear pickle jars, sorted by race and grade. They picked the names all weekend, as teachers watched the process on television. Although the drawing was designed to be random, Jones lost many of its best staff, including department heads in English, math and science.

From “Jones High School Centennial Celebration” (1995)

Pictured: Page from the 1972 Jones High School Yearbook

Integration in Orlando

Although the drawing was designed to be random, Jones lost many of its best staff, including department heads in English, math and science. The music department was decimated: both band director James “Chief” Wilson, with 20 years at Jones High School, and choir director Edna Hargrett were transferred. “All pressure was put on Jones,” said Wilbur Gary, then principal of the school. He later negotiated to get Wilson and Hargrett back.

From “Jones High School Centennial Celebration” (1995)

Pictured: Page from the 1973 Jones High School Yearbook

Integration in Orlando

The new rules meant that Jones would always have a predominately white teaching staff. The student body, however, never truly integrated. White students stayed away by using academic transfers and false addresses, some parents sent their children to private schools. Of 619 white students assigned to attend in 1970, only 183 arrived. The number dropped to 146 in 1971.

Jones’ enrollment plummeted. Many black students were sent to closer schools. Even some who lived near Jones left for white schools with less vocational emphasis. Still other students left the neighborhood when the East-West Expressway was built displacing about 400 potential Jones students. From 1969 to 1973, the school lost more than half its enrollment of 1,900 students.

From “Jones High School Centennial Celebration” (1995)

Pictured: “Our School Song” a photo of an integrated class assembly in the 1970 Jones High School Yearbook, Jones High School Historical Society

Closing Threats of Jones Current School

Rumors spread in 1973 that the school board was again considering closing and converting Jones. The board denied the rumors in a stormy meeting with black parents, but the notion would resurface several more times in the next decade. By 1995 attendance was slowly increasing.

From “Jones High School Centennial Celebration” (1995)

Pictured: Inside a Jones High School classroom. From Jones High School Yearbook 1972, Jones High School Historical Society

Integration’s Impact

We had kids leaving in the 11th grade to go to college, remembers Ernestine Embry, a Jones teacher for 52 years and a 1938 graduate. "When integration hit, we took a spin downwards." That belief is more perception than fact, insists Gary Orfield, a professor of education and social policy at Harvard University. When schools like Jones were supposedly at their prime, black achievement was down, Orfield says. Fewer blacks graduated from high school and college before desegregation. In the 1970s, Jones was a school in trouble, the subject of constant speculation it would close. It was a fate that befell most all-black high schools in Florida. Many became junior highs or vocational schools. In 1974, the superintendent recommended turning Jones into a vocational-technical center; black groups protested because they wanted tougher academics. Jones never became a vocational school, but its vocational facilities were upgraded, and a third of its students took vocation classes. The low point in the school’s academic history was in 1977 when most juniors failed the state competency test.

From “Jones High School Centennial Celebration” (1995)

Pictured: Jones High School from Jones High School Yearbook 1985, Jones High School Historical Society

Dr. J. B. Callahan Neighborhood Center

In 1970 Callahan Elementary closed which was the site of the old Jones High School along with many other historic black schools in Orange County. Concerned residents lobbied the city to keep the building as a community center. On May 24, 1986 the Callahan Center opened after major renovations. The original Jones High School building was razed except for the front façade. Georgia Woodley, president of the Callahan Neighborhood Association when asked about the renovation plans at the time told the Orlando Sentinel, “residents have asked that the wall be kept so the community will know it was the Callahan School or the old Jones High School.”

Pictured: Current photo of Dr. J. B. Callahan Neighborhood Center, Source RICHES Mosaic Interface™

The Ellen DeGeneres Show

In 2018, Andrea Green and Jamal Nicholas, Choir Director and Band Director at Jones High School, were invited to the Ellen DeGeneres Show. Ellen surprised Jones High School with a check for $100,000. The school was invited to perform at Carnegie Hall in April of 2018. Jones High School was one of only three schools in the country to receive an invitation for both their choir and band programs.

Pictured: Clip from The Ellen Show featuring Jamal Nicholas and Andrea Green.

Source: EllenTube

Click "View More" to watch the clip.

Where We Stand

In the 1950s and 1960s, before a federal court ordered Orange County to integrate its schools, Jones High was one of only four all-black high schools. Jones, whose alumni have the indefatigable loyalty found at schools such as Notre Dame, was the only black school to survive after desegregation. The school's alumni include judges, professional athletes, educators at every level and many of the best known local government officials. Today, many return for Jones' annual role model day. Teachers put high demands on students.

Pictured “Jones High School Graduation, n.d. Jones High School Historical Society”

For the Future The Jones High School Historical Society

The Jones High School Historical Society Inc. was formed in 1997. The Historical Society opened and maintains a museum on site at Jones High School so that students can continue to learn the important history of Jones High School to the greater Orlando community and to themselves as future alum of the historic school.

Pictured: From Left to Right: Samuel Lumpkin, Leroy Argett Jr., Earlene Tillman, Robert Reed, Orange County Schools Superintendent Dennis Smith, Audrey Reicherts, James "Chief" Wilson